The Constant Spring Hanger: Engineering Magic

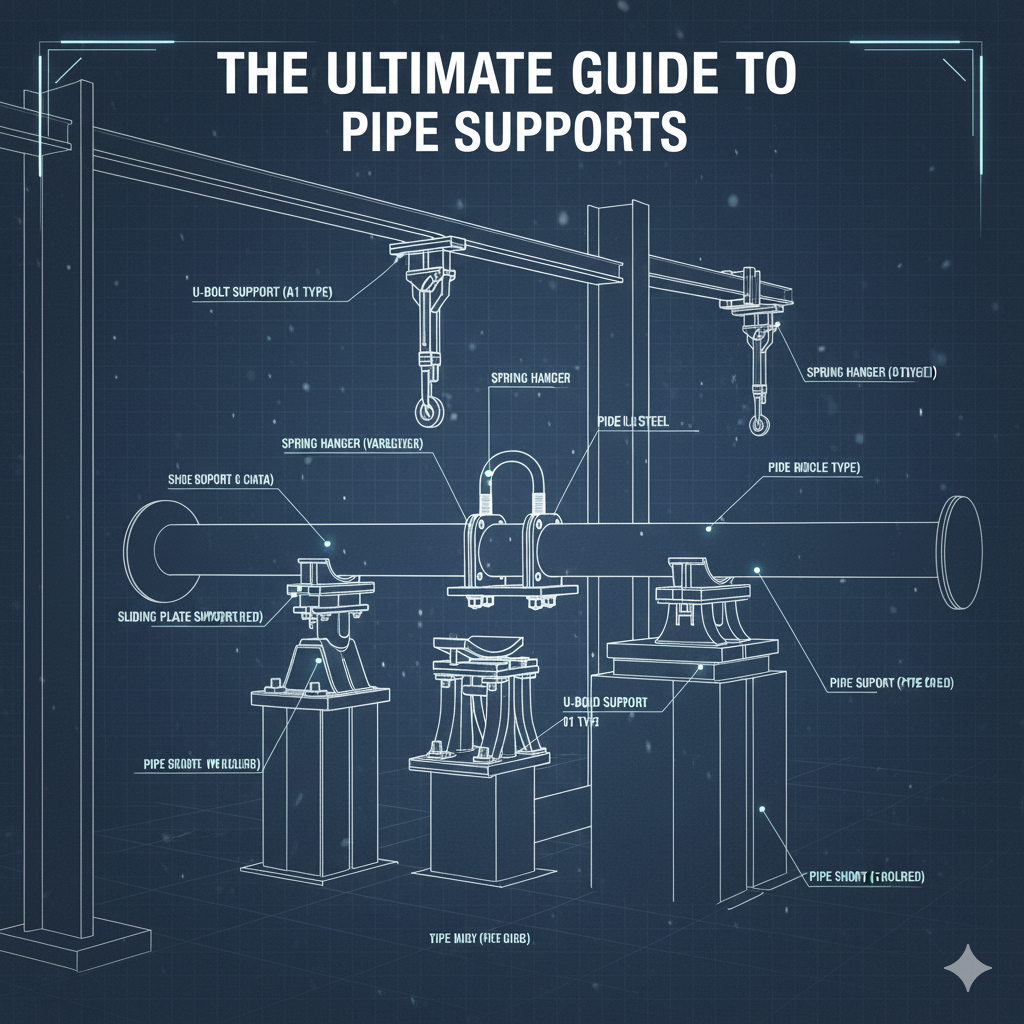

Pipe Supports

1. Definition & Function Deep Dive

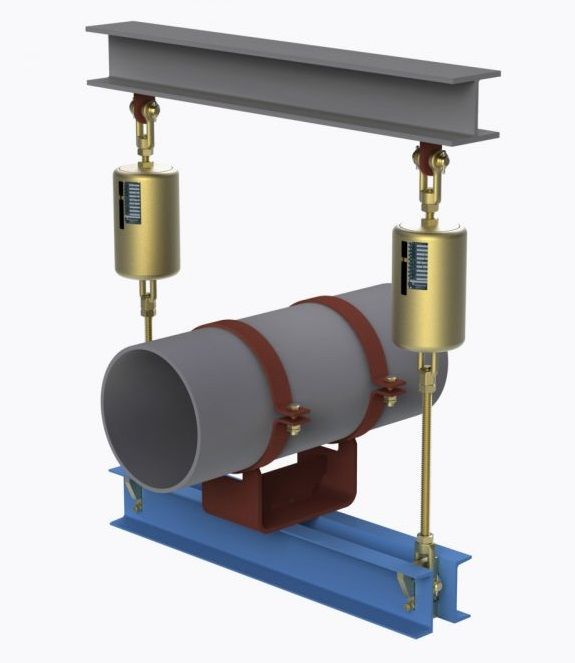

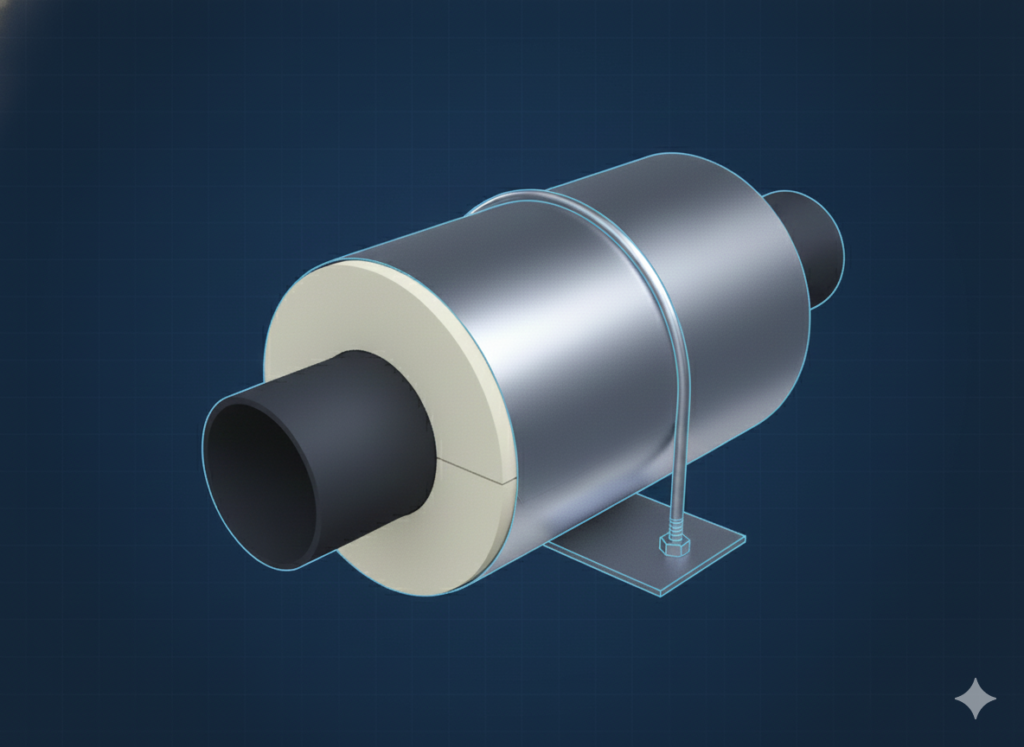

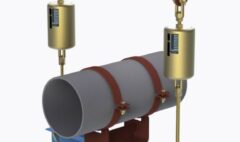

When vertical thermal movement is large (over 2-3 inches), or the pipe is connected to extremely sensitive equipment (like a reactor vessel or a high-speed turbine), even the 25% load variation of a variable spring is unacceptable. The “Constant” is a complex mechanical device designed to exert the exact same lifting force regardless of where it is in its travel range.

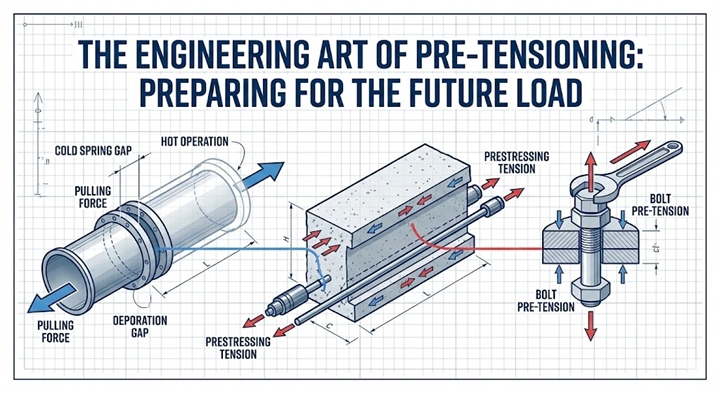

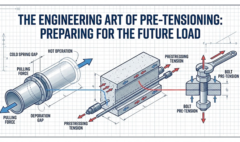

2. The Physics (How it works)

It doesn’t defy physics; it uses geometry. It employs a spring coupled to a cam or a lever arm mechanism. As the pipe moves and the spring compresses (increasing its raw force), the lever arm geometry shifts to decrease the mechanical advantage exactly proportionally. The net result at the pipe attachment point is a constant upward pull.

3. Real-World Challenges

- Cost & Size: They are significantly larger, heavier, and much more expensive than variable springs.

- Maintenance Nightmare: If a piping system weighs slightly more than calculated (e.g., thicker insulation was used), the constant support will “bottom out” or “top out” and fail to function. Adjusting the load setting in the field on a live plant is a dangerous, complex task requiring specialized vendor technicians.

4. Bottom out and Top out

A Constant Spring Hanger is designed to provide a uniform supporting force throughout its entire range of travel. However, it can fail to do so if it reaches the physical limits of its mechanism. This is known as “bottoming out” or “topping out.”

1. Bottomed Out Condition

A constant spring support “bottoms out” when the pipe it is supporting moves further down than the hanger was designed to accommodate. In this state, the hanger has reached the lower limit of its travel range and can no longer provide a constant force.

Conditions: This occurs if the actual weight of the piping system is significantly heavier than the calculated design load, or if the pipe’s downward thermal movement is greater than the hanger’s designed travel range.

Consequence: The spring mechanism compresses to its limit and hits a hard stop. The hanger effectively becomes a rigid rod, transferring any additional downward load or movement directly to the supporting structure, potentially causing overloading.

2. Topped Out Condition

Conversely, a constant spring support “tops out” when the pipe moves further up than the hanger was designed for. It reaches the upper limit of its travel range.

Conditions: This happens if the actual weight of the piping is significantly lighter than the calculated design load, or if the pipe’s upward thermal movement is greater than the hanger’s designed travel.

Consequence: The internal mechanism hits its upper stop. The hanger can no longer lift the pipe. If the pipe continues to try to move up, it will lift off the support entirely, meaning the hanger is no longer carrying any load, and the pipe’s weight is transferred elsewhere in the system.