Policy & Economics of Renewable Energy

Renewable Energy

Introduction: The Invisible Hand turns Green

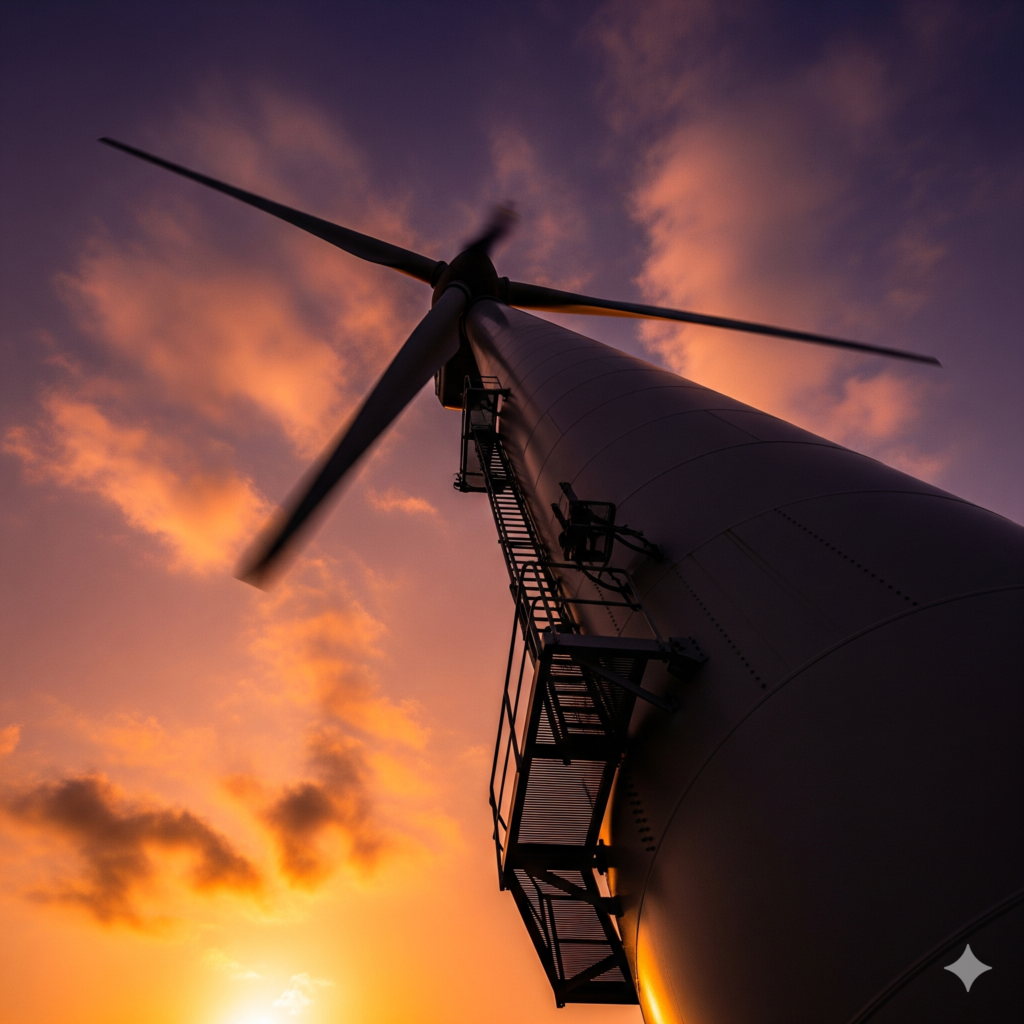

For decades, the primary argument against renewable energy was cost. Critics argued that solar and wind were expensive luxuries that required heavy government subsidies to survive. Today, that narrative has fundamentally flipped. In many parts of the world, building a new solar farm is now cheaper than simply operating an existing coal plant.

However, the energy market is not a free market in the traditional sense. It is a complex web of regulated monopolies, subsidies, geopolitical strategies, and long-term infrastructure investments. Understanding the transition requires more than just engineering knowledge; it requires a grasp of the policy frameworks and economic metrics that dictate which projects get built and which get cancelled.

In Part 9 of our series, we leave the physics behind to explore the finances. We will dissect the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE), analyze the shift from Feed-in Tariffs to Auctions, and look at how global capital is mobilizing through Green Bonds and carbon pricing.

The Gold Standard Metric: LCOE

To compare the cost of a nuclear plant (which runs 24/7 for 60 years) with a solar farm (which runs 8 hours a day for 25 years), engineers and financiers use a metric called the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE).

Defining LCOE

LCOE represents the average revenue per unit of electricity generated ($/MWh) required to recover the costs of building and operating a generating plant during an assumed financial life and duty cycle.

- Formula: Total Lifetime Cost / Total Lifetime Energy Production.

- The Trend: According to Lazard’s LCOE analysis, the cost of utility-scale solar PV dropped by nearly 90% between 2009 and 2020. This drastic reduction is due to economies of scale (manufacturing millions of panels), technological efficiency improvements, and competitive supply chains.

The “Value” Deficit

While LCOE is critical, it isn’t perfect. It treats all electrons as equal. However, an electron produced by solar at noon (when electricity is cheap) is less valuable to the grid than an electron produced by a gas plant at 7 PM (when demand peaks). As renewable penetration increases, we are moving beyond simple LCOE to “Levelized Cost of Storage” (LCOS) and “Value-Adjusted LCOE” to account for when the power is delivered.

Policy Mechanisms: The Carrots and Sticks

Government policy acts as the catalyst for energy markets. The mechanisms used have evolved as the technologies have matured.

1. Feed-in Tariffs (FiT)

In the early days (2000s), governments wanted to kickstart the industry. They offered Feed-in Tariffs, guaranteeing developers a fixed, premium price for every kWh of renewable energy they generated for 20 years. This provided total security for investors and launched the solar boom in Germany and Spain.

- Status: Mostly phased out. Solar is now cheap enough that it doesn’t need guaranteed premium prices.

2. Auctions and Tenders

Today, most governments use competitive auctions. The government announces a need for 1GW of solar power, and developers bid the lowest price they are willing to accept.

- Impact: This drives prices down aggressively. Recent auctions in the Middle East and Portugal have seen record-breaking low bids (under $0.02/kWh), proving that renewables are the cheapest power source on Earth.

3. Tax Credits (ITC/PTC)

In the United States, policy relies heavily on tax incentives. The Investment Tax Credit (ITC) allows developers to deduct a percentage of installation costs from their federal taxes. This attracts “Tax Equity” investors—large banks or corporations looking to lower their tax bills by funding green projects.

4. Carbon Pricing (The Stick)

Economists argue the most efficient way to decarbonize is to put a price on pollution.

- Carbon Tax: A direct fee imposed on burning fossil fuels ($/ton of CO2).

- Cap-and-Trade: The government sets a limit (Cap) on total emissions and issues permits. Companies can buy and sell (Trade) these permits. If a factory reduces emissions, it can sell its extra permits to a dirtier factory. This creates a market incentive to be green.

Financing the Future: Green Bonds and PPAs

The global transition requires trillions of dollars in upfront capital. Innovative financial instruments are bridging the gap.

Green Bonds

A Green Bond is a fixed-income instrument designed specifically to support climate-related projects. Issued by governments or corporations, they function like regular bonds but come with a promise: the proceeds will only fund certified green projects.

- The “Greenium”: Because there is so much demand from institutional investors (pension funds, insurers) to hold sustainable assets, Green Bonds often have a slightly lower yield (interest rate) than regular bonds. This “Greenium” means it is cheaper for companies to borrow money for green projects than for fossil fuel projects.

Corporate PPAs

Big tech companies (Google, Amazon, Microsoft) are major drivers of renewable growth. Through Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs), these companies sign long-term contracts to buy electricity directly from a wind or solar farm developer.

- Virtual PPA: Often, the company doesn’t physically get the electrons. Instead, it’s a financial hedge. The developer sells power to the grid at market price. If the market price is low, the corporate buyer pays the difference to ensure the developer stays profitable. If the market price is high, the developer pays the corporate buyer. This guarantees a stable income for the project, allowing it to get built.

Common Pitfalls

- Policy Uncertainty: The biggest enemy of investment is not high cost, but uncertainty. If a government constantly changes its subsidy rules or retroactively cuts tariffs (as happened in Spain and Italy), investors flee, and the cost of capital skyrockets.

- Cannibalization: In markets with too much solar, the price of electricity crashes to zero (or negative) during sunny afternoons. Solar farms essentially “cannibalize” their own revenue. This emphasizes the need for policy that supports storage, not just generation.

Example: The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)

The 2022 US Inflation Reduction Act is the single largest investment in climate and energy in American history. Rather than using a carbon tax (stick), it uses $369 billion in subsidies and tax credits (carrots) to stimulate manufacturing and deployment. It has sparked a global “arms race” for green tech, with the EU responding with its own Green Deal Industrial Plan to keep clean energy manufacturing from moving to the US.

Conclusion

The economics of renewable energy have passed a tipping point. We are no longer debating if renewables are affordable; we are figuring out how to deploy the capital fast enough. By aligning LCOE realities with smart policy frameworks and innovative financing, the world is shifting the financial weight of the global economy toward a sustainable future.